Bringing Back the Bison

Tens of millions of wild bison once freely roamed across North America. Now, scientists prepare for their return.

By Alix Morris

The Missing Force of Nature

Narcisse Blood was a big man, the kind of man who, when he stood up, filled a doorway. A respected leader and member of the Kainai First Nation in Southern Alberta, also known as the Blood Tribe and part of the Blackfoot Confederacy, Narcisse believed in the power of relationships to guide us. ‘If you just listen to the relationships,’ he said, ‘if you honor them, then it’s like the stars – everything will align and work the way it has always worked.’

His friendship with Dr. Cristina Eisenberg began – as many relationships do – on Facebook. In 2013, after he finished reading Cristina’s book The Wolf’s Tooth, Narcisse sent her a Facebook message: ‘I read your book and want to be your friend. Can you show me a trophic cascade?’ A trophic cascade, which Cristina describes in her book, refers to the relationships between species within a food web. Cristina was surprised to hear from this highly respected Kainai elder, and accepted his friend request immediately.

“There are certain periods in time that are a nexus, where all of these things come together at once,” said Cristina, Earthwatch’s Chief Scientist and Principal Investigator of the expedition Restoring Fire, Wolves, and Bison to the Canadian Rockies. “That’s exactly what happened.”

Several months later, Cristina invited Narcisse and his wife, Alvine Mountainhorse, to her field site in Alberta’s Waterton Lakes National Park to show him her research. In this biodiversity hotspot, Cristina and her team study the relationships between wolves, elk, fire, grass, and aspen. They spoke about where the wolves had been, and how many elk there were, and where aspen had spread into the grassland. They spoke of the fires they had set to maintain the ecosystem. She then turned to Narcisse and Alvine. ‘What do you think is going on here?’ she asked. ‘Well, there’s something missing,’ Narcisse said.

Tens of millions of wild bison, sometimes referred to as buffalo, once roamed the landscape across North America, including in and around Waterton. But in the mid-1800s, Euro-American settlers decimated the population, effectively “de-wilding” the landscape. Today, not a single bison remains in the park.

Our songs, our ceremonies are calling out for the buffalo to return. Bring them back! Bring them back here. Let’s take these fences down. We need them. Probably we need them more than they need us.

—Narcisse Blood, Facing the Storm: Story of the American Bison

That night at the Waterton research house, Cristina prepared dinner for Narcisse and Alvine. She and her field crew rolled out pizza dough, topping the pies with elk meat Cristina had hunted. For hours, they told stories about wolf encounters, elk hunts, and the importance of science to understand relationships in nature. They spoke about the role that free-ranging bison once played in this ecosystem.

At the end of the night, Narcisse hugged Cristina goodbye and thanked her for the meal. Before he left, he turned and said, ‘I want you to do the work that you’re doing...on our land.’

The Blood Timber Limit

For more than 50 years, Blackfoot land in Alberta, known as the Blood Timber Limit, had been closed off to anyone who was not a member of the tribe. For years, non-tribal members had destroyed the tribe’s sacred forests and lush elk meadows through illegal logging and by planting non-native invasive grasses. In a few parting words, Narcisse had granted permission for the first non-tribal member since 1960 to collect scientific data on that land. Cristina could now expand her research into a critical ecosystem, while working in partnership with the Kainai and tribal leaders, including Leroy Little Bear, Clo-Ann Wells, Mike Bruised Head, Kansie Fox, and Elliot Fox.

Today, Waterton Lakes National Park is one of the wildest, most ecologically intact North American landscapes. Within this diverse ecosystem, Cristina’s research team, which includes scientists David Hibbs and Curtis Edson, field technicians, park rangers, and Earthwatch volunteers, have combined forces to untangle the relationships between key forces of nature – wolves, elk, and fire. Now, they’re looking into the role that bison could play in helping maintain this delicate ecosystem as plans to reintroduce bison to this landscape begin to materialize. By partnering with the Kainai First Nation and extending the field site into the Blood Timber Limit, the research could help to inform not only Waterton managers and the conservation community, but Kainai leaders who are maintaining tribal lands.

That dinner in Waterton was the last time Cristina would see Narcisse. In 2015, he was killed in a tragic car accident in Saskatchewan. But his legacy lives on. “The tribe talks about him today as if he’s still alive,” said Cristina. “‘His death brought us all together,’ they told me. That’s his legacy.”

De-Wilding

Tens of millions of bison once roamed through North America, massive herds thundering across the Great Plains, leaving clouds of dust in their wake. But as Euro-American settlers moved west, the U.S. Army launched a campaign to eliminate bison in an effort to exert control over Native American tribes that depended on bison for food, clothing, shelter, tools, and myriad other materials, in addition to their spiritual connection to this animal. Bison habitat was converted into agriculture fields, and the species was hunted to near extinction. By the late 1880s, the iconic species that once dominated the landscape had been reduced to just 1,000 animals.

The primary cause of the buffalo’s extermination, and the one which embraced all others, was the descent of civilization, with all its elements of destructiveness, upon the whole of the country inhabited by that animal.

—William T. Hornaday, The Extermination of the American Bison

In the early 1900s, a group of conservationists led by zoologist and taxidermist William T. Hornaday, with support from Theodore Roosevelt and the Boone and Crockett Club, launched a movement to save the bison from extinction. The Boone and Crockett Club, North America’s oldest wildlife and habitat conservation organization, was instrumental in preventing the extinction of bison among many other species, including wolves, caribou, and mountain goats. These conservationists helped to ensure the few remaining bison were transferred to protected land in Yellowstone National Park and Canada’s Great Slave Lake, while others were kept on private land and in zoos.

Over the years, as the captive bison population has grown, park managers have faced considerable challenges keeping the animals confined to the parks, where they are protected from hunting. “Bison naturally migrate,” said Cristina. “A place like Yellowstone is a postage stamp for bison. These animals make up to 600-mile migrations. It’s their instinct; it’s programmed in their DNA.”

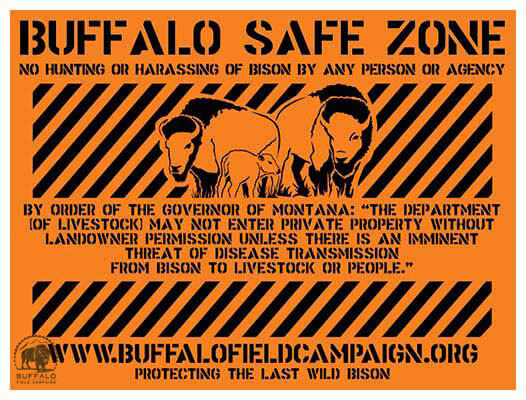

Outside of Yellowstone, conservation activists working with the Buffalo Field Campaign have positioned themselves along the park’s boundaries, attempting to herd any bison that approach the border back onto protected land, in some cases placing themselves between a bison and a bullet.

Although the herds are protected within the confines of the parks, bison are unable to fulfill their ecological role if they can’t migrate. “The ecological benefits of bison as a keystone herbivore have to do with their ability to move,” said Cristina. “They stay briefly in an area, fertilize the crap out of the system, and then leave. And along comes the next wave of herbivores and everyone’s happy.” Bison also trample aspen, helping to keep grasslands open.

Back in Waterton, to account for this missing ecosystem service, park managers have been setting prescribed fires to burn up overgrown aspen to create more grass. Free-ranging bison would help to create a more sustainable solution to the problem. Fire, an integral component of this system for the last 10,000 years due to the fires indigenous people would set to help them hunt and to improve habitat for bison, would remain a part of the equation, but with bison present, they would be needed less frequently.

So what does it take to return these animals to their original habitat?

The Buffalo Treaty

In 2014, Leroy Little Bear, an eminent Kainai elder from the Blackfoot Confederacy and former director of the Harvard University Native American Program, led the drafting of a historic treaty known as the Northern Tribes Buffalo Treaty, which called for the return of wild bison to tribal lands to fulfill the animal’s ecological, cultural, and spiritual role. With support from the Wildlife Conservation Society, members of eight U.S. Tribes and Canadian First Nations signed the Treaty in September 2014 in Browning, Montana on Blackfeet territory – the first peace treaty of its kind among those tribes in more than 150 years. Today, there are more than 20 signatory tribes.

Bison were their world. Their religious beliefs, their subsistence, their culture – everything revolved around bison. So the extinction of bison was profound. A major healing is taking place. At the same time, we realized that we can’t address climate change effectively unless we try to heal the damage done to ecosystems. Bison are the missing piece.

—Dr. Cristina Eisenberg

In February 2015, Parks Canada announced their plan to reintroduce free-ranging bison to Banff National Park – an initiative that launched just months ago, in February 2017.

Hooves on the Ground

One by one, helicopters lowered the three-meter-long shipping containers into an enclosed pasture in Panther Valley in Canada’s Banff National Park. The transport crew steadied the containers as they landed and pulled open the doors. Sixteen young bison, six bulls and ten pregnant females selected from a genetically pure “seed herd” in Elk Island National Park, galloped out into the snow-covered pasture – taking the first steps in their journey back to the wild.

This initial release is part of a wider effort to reintroduce bison to regions they once inhabited in the U.S. and Canada, including Waterton. A captive herd of over 80 young bison awaits release into the Badger-Two Medicine area, in northwest Montana. This bison rewilding is being led by Wildlife Conservation Society senior ecologist Keith Aune and is called the Iinnii Initiative (iinnii means bison in Blackfoot).

Help to Bring the Bison Home

Join Cristina and her team in the field on the expedition Restoring Fire, Wolves, and Bison to the Canadian Rockies to support what is being celebrated as one of the most significant conservation efforts of our time.

Work alongside members of the Blackfoot First Nation to collect data that will shape national conservation and management policies in preparation for returning bison to Waterton Lakes National Park and the surrounding region. Join scientists, conservationists, policy makers, and indigenous people and help to bring the bison home.

If you have any comments or questions related to this story, please contact us at communications@earthwatch.org. We welcome your feedback.