Using Cutting-Edge Technology to Protect the Sharks of Belize

By Dr. Demian Chapman

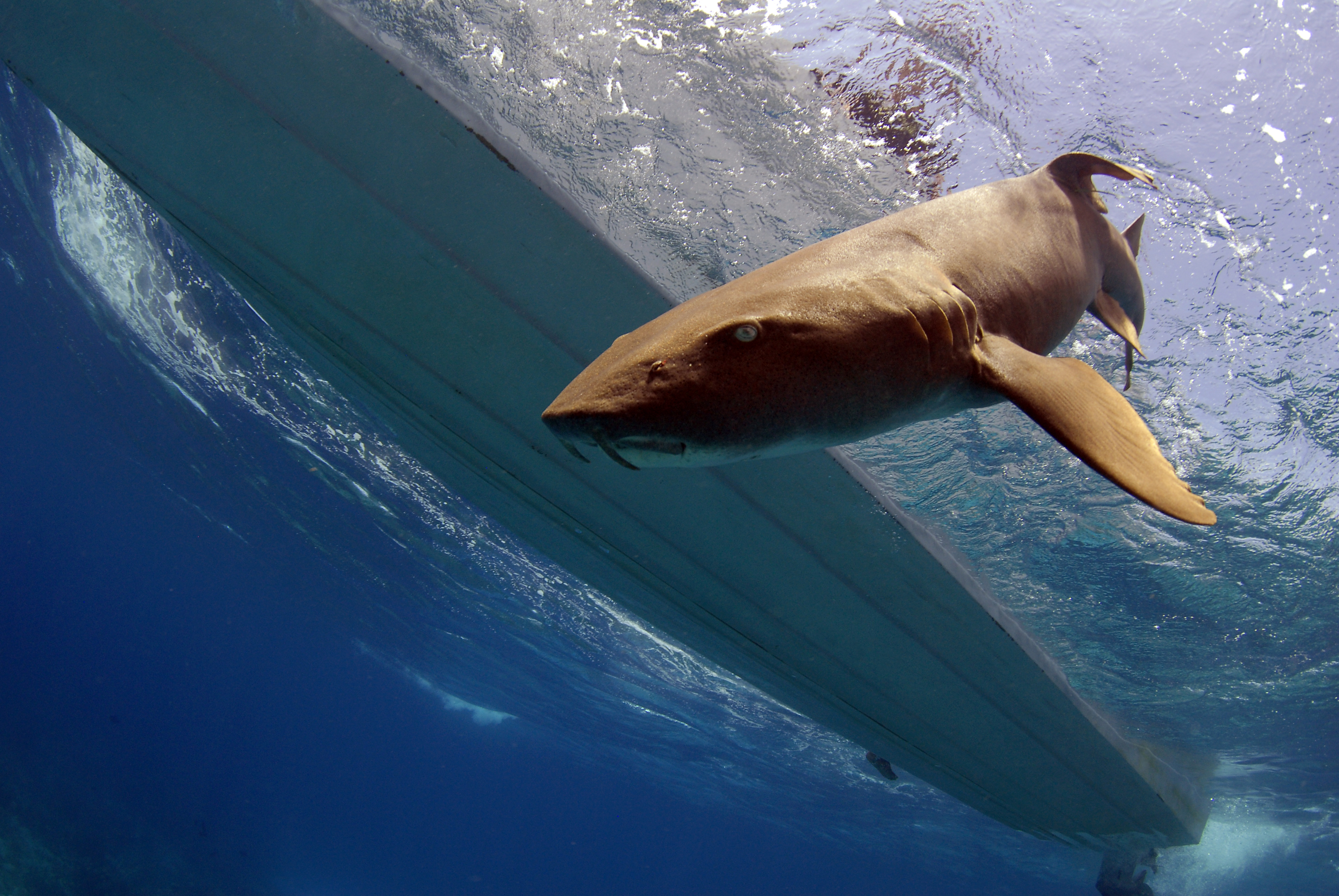

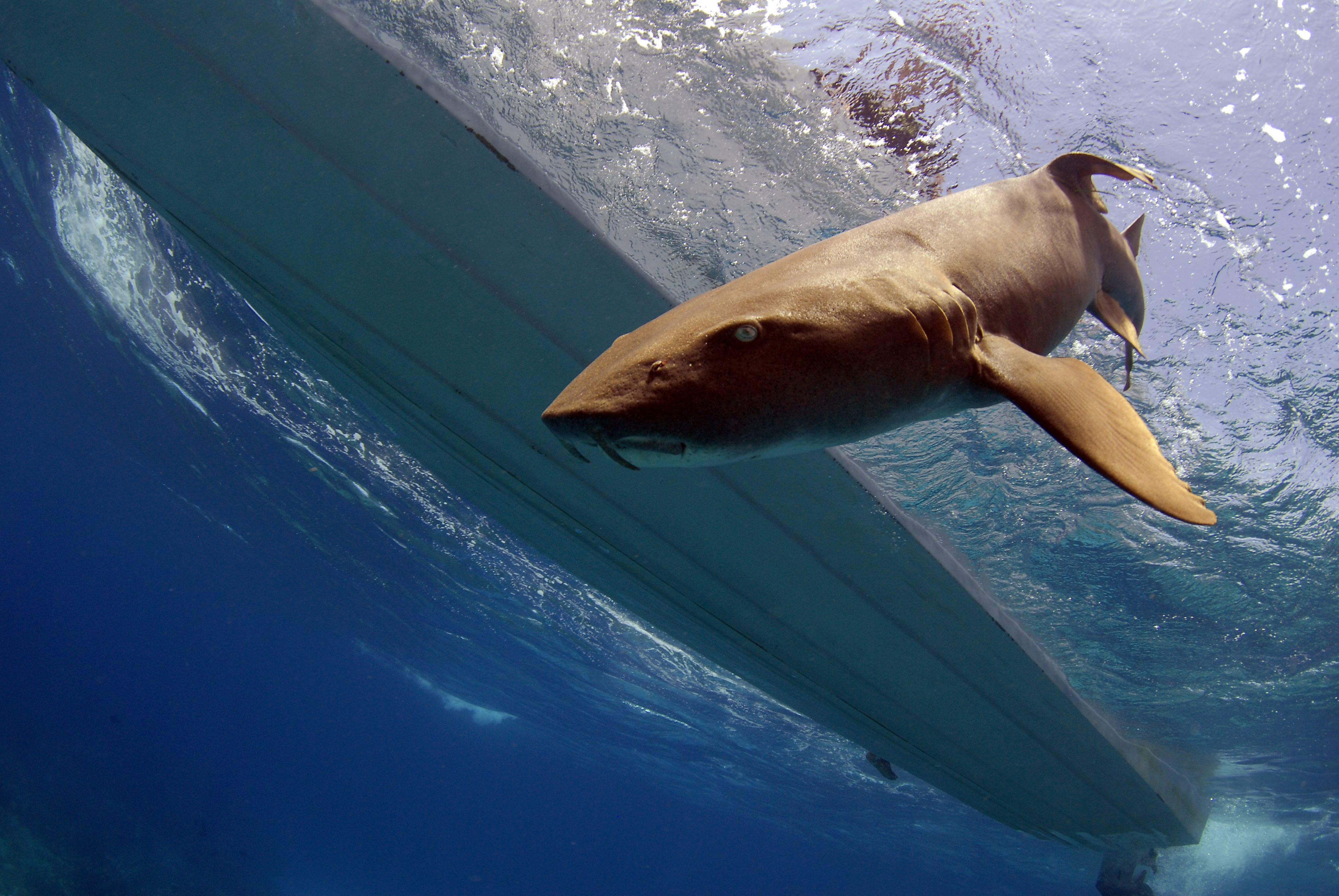

Dr. Demian Chapman has devoted his career to protecting the sharks around the world, including those living in Belize. He’s teamed up with fishermen and the government to try to strengthen shark fishing regulations and monitor marine reserves. Now he is engaged in the first study of its kind: measuring how long an overfished shark population takes to recover in a newly minted marine reserve, Southwater Caye. He is also investigating other ways that marine reserves affect sharks and their close cousins, the rays. To do this, he will rely on cutting-edge technology.

My name is Demian Chapman. I am an Associate Professor at Florida International University and the Lead Scientist of the Earthwatch Project Shark Conservation in Belize. I have been working on a wide variety of conservation-related research topics for the past two decades, but of all of my projects, I probably feel most at home when I am studying sharks in Belize. This stems from the strong sense of family I have developed with the Belizean people, especially my brothers-from-another-mother and research partners Captain Norlan Lamb and First Mate Ashbert Miranda, as well as the deep love I have for this tiny nation in the Caribbean.

I first came to Belize in July 2000. Now, more than a decade and more than 20 expeditions later, I have fallen in love with this country, its barrier reef ecosystem, and its people. Since I was a small boy in New Zealand, sharks have been my passion. When I arrived in Belize, one would only occasionally see sharks in the fish market, and the prices paid for them were modest. This has changed. Today, fishermen are exploiting sharks in Belize almost without any regulation. My team has deployed baited remote underwater videos (BRUVs)—underwater video traps to count sharks and other fish—on reefs where gillnets and fishing are allowed and found that sharks are nearly absent on these reefs.

Thankfully, there is still hope for the sharks of Belize.

Our BRUV deployments have found robust and thriving shark populations on reefs where gillnets and/or fishing are banned—marine reserves. It is our goal to survey these no-fishing zones and to investigate how and why they are working for shark conservation. We also aim to elucidate the ecological role of sharks through chemical analysis of their tissue. To these ends, we have thrown on our work gloves to deploy BRUVs and catch sharks on some of the most beautiful reefs in the Caribbean.

Most importantly, we will be communicating our results to the people of Belize so that they can take action. With the help of Earthwatch volunteers, we will ensure that the coral reefs of Belize remain a rich hunting ground for these majestic predators.

Technology in Conservation Research

This year I am really excited to be asking new questions that will involve introducing some new technology to our research portfolio. The answers will address gaps in our understanding of the conservation needs and ecological role of sharks and rays on coral reefs, which will help us better manage these animals in Belize and beyond.

Recent analysis by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) has revealed that the world is rapidly losing its sharks and rays. This is a serious problem and may trigger strong changes in ocean ecosystems.

We know very little about the role of sharks and rays in marine ecosystems and how humans affect these roles. Most people have probably heard that the overfishing of sharks on the east coast of the U.S. led to a ray population explosion. The rays then ate all of the shellfish, leading to the collapse of a century-old fishery. Simple right? Well, perhaps not. One study (Grubbs et al. 2016) showed there are a number of substantial problems with this interpretation, ranging from questions about whether sharks eat enough rays, to the rays themselves being unable to reproduce fast enough to match the purported population “explosion.”

Science is now going back to the drawing board to learn about how sharks, rays and humans interact with one another and their environment.

This is where we come in at Shark Conservation in Belize. Funded by Earthwatch and the Vulcan Foundation, and supported in the field by more than a hundred Earthwatch volunteers over the years, we have used BRUVs to survey sharks and rays in marine reserves and fished areas throughout Belize. Our key discoveries have been that Caribbean reef sharks are significantly more common inside Belize’s marine reserves and, as a result, stingrays in these management zones fear being eaten by them. So much so that they avoid going into deeper water where the reef sharks live.

These studies show that human activities like fishing or establishing a marine reserve on a reef can alter local densities of sharks, which then cause shifts in habitat use by rays.

As our project enters its seventeenth field season in 2016, we are going to probe this interaction between people, sharks and rays even more deeply. First, we want to know whether there are reef sharks inside reserves because they spend their whole lives there, living and breeding under a sort of protective umbrella. An alternative possibility is that reef sharks are born all over Belize, but end up concentrating inside reserves where the feeding is good because there are more fish. To answer that question we need to track individual reef sharks from birth to after they mature to see if they spend their lives on the reef where they were born. We will start doing this in the summer of 2016 at Glover’s Reef Marine Reserve (Teams 1-3). This will entail catching young reef sharks and surgically implanting acoustic transmitters. Each transmitter emits a unique coded signal every few minutes that can be picked up by receivers that we will anchor on the reef. The receivers will pick up each shark’s unique signal and record where the individual is and when. The transmitters will last for about ten years, more than enough time to see if the baby sharks born at Glover’s reef grow up there.

Our second question revolves around stingray behavior in the presence or absence of sharks. Our baited remote video data has shown us that the rays mostly stay in the shallows on reefs where sharks patrol the deeper reef. We are interested in figuring out if they feed less and hide more in these areas. To answer this question we will be fitting southern stingrays with accelerometer tags during Teams 3 and 4 at Glover’s Reef (where there are sharks) and Southwater Caye (where sharks are nearly absent due to fishing). Accelerometer tags measure movement.

You might not know this but you are probably in possession of an accelerometer right now. Can you guess where it is?

It’s in your smart phone. An accelerometer makes the screen rotate when you move your phone. This same technology will record the body angle and swimming speed of free living stingrays and tell us how much time they spend hiding or resting, moving, and feeding. We will then be able to see if stingrays living in marine reserves where sharks are still common spend more of their time buried in the sand and less time eating worms, small fish and shellfish. If this is the case, it could alter how rays affect the seafloor and the animals and plants that live there.

As we purchase our acoustic tracking gear and accelerometer tags to take to Belize this summer, I am excited to think that they will help us learn more about the secret lives of sharks and stingrays.

I am sincerely grateful to the Earthwatch volunteers that have helped us get to the point to be able to ask these questions. I also look forward to working with the volunteers that will help us answer them.

You can join this expedition and help Dr. Chapman with is research! Secure your spot on the expedition Shark and Ray Conservation in Belize.