.

An Eruption of Citizen Science in Nicaragua

The story of a volunteer’s innovative contribution to volcano research.

By Keegan Dougherty

When citizens meet scientists, exciting things happen. Massive data sets are collected, critical funding is raised, and ideas are shared. On the expedition Exploring an Active Volcano in Nicaragua last March, I witnessed an unexpected synergy of a citizen and a scientist collaborating to solve a simple research problem.

.

What resulted was a pioneering use of a brand new software that may change the study of extinct lava tubes for volcanologists everywhere.

.

.

On our first day assisting the Earthwatch scientists on the slopes of Masaya, Dr. Guillermo Caravantes, one of the lead volcanologists on the expedition, asked if any of the volunteers were feeling particularly intrepid that day. Guillermo recently completed his PhD studying Masaya with Dr. Hazel Rymer at the Open University. Now a fully-employed geoscientist, Guillermo was taking time-off from work to tackle a completely different type of volcanology research. To start, he needed two volunteers in a search for entrances to empty lava tubes—cave-like channels formed by earlier lava flows—under the thorn-ridden dry tropical forests flanking the northeast side of the active volcano.

.

I jumped at the opportunity to join Guillermo for our first adventure of the expedition.

.

Cliff Gill, a volunteer who splits his time between Missouri and Alaska as an aerial survey pilot, politely volunteered when no one else did. We were led into the brambles by a Masaya National Park Ranger, Carlos Molina Palma, who had been patrolling the park for over a decade and knew the trails well.

.

.

Tramping through the forest after Carlos turned out to be crucial for the research. The lava tubes have had thousands of visitors in the centuries since their formation, mostly vampire and insectivorous bats, but also the Contras, film-maker biologists, and pre-Columbian peoples. The previous visitors’ respective guano, footprints, rubbish, and pottery fragments still litter the floors of many lava tubes. Yet despite all this traffic, the tubes have never been mapped. In fact, the only known map of the lava tubes was a mental one, resting between Carlos’ ears.

These cooled lava tubes were formed when bubbling basaltic lava poured out of the Masaya crater and flooded the its flanks. As the lava crept down slope, the top of the flow cooled faster forming an insulating roof over the molten lava below. The old tubes left behind from previous flows can act like underground superhighway for future eruptions, allowing the lava to flow freely without the traffic and obstacles on the surface.

Once Guillermo took GPS coordinates of all of the lava tubes that Carlos showed us, the task was simple – Guillermo would bring back volunteers every day to each cave entrance to measure the dimensions, slope, and angle of the tube within. Simple enough, right?

.

.

This is where the magic happened. As a caving enthusiast and an aerial surveyor, Cliff is tuned-in to the latest software releases in remote sensing, including that a new tool developed by Agisoft which creates 3-D renderings of interior spaces from photos taken by a regular digital camera. Cliff had been posting about his use of the software in online caving forums and message boards to see if this software could gain traction, but somehow it hadn’t garnered much interest.

.

.

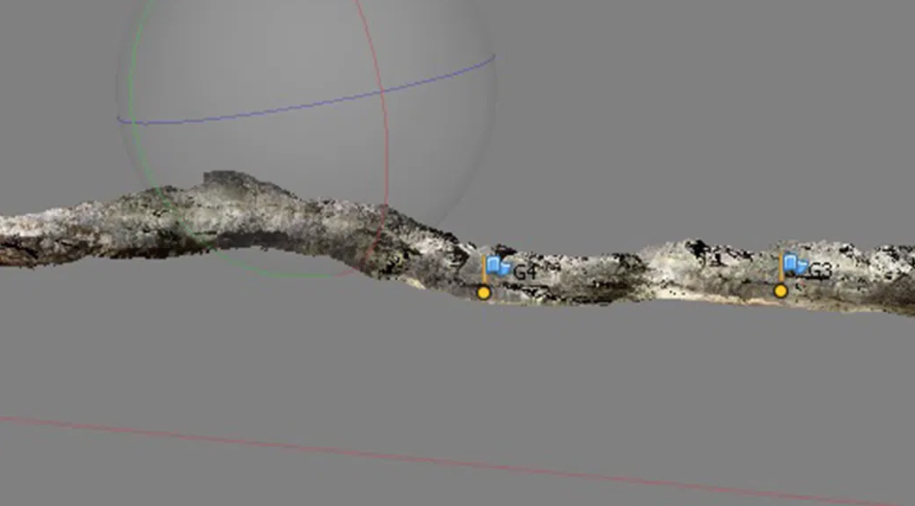

As we peered into the first dark, bat-filled lava cave, a light must have gone off in Cliff’s mind—he could use his high-powered caving lights to illuminate the caves, snap photos with his digital camera, and render the images on his laptop back at the hotel. By coincidence, Cliff had brought his laptop, with the Agisoft PhotoScan software already loaded; he had no idea this was part of the research—this was serendipity. When Cliff shared his revelation, I remember Guillermo asking a few clarifying questions, then his look of disbelief, repeating something to the effect of “Wow, this changes everything” as the realization of what was possible sunk in.

.

.

The previous week, the best Guillermo could do was sketch the dimensions of tube interiors. Now, with Cliff’s ingenious use of the software, he could build a 3-D tour of the lava tubes and create a detailed map with existing maps to share with the National Park. Guillermo will soon publish his findings and volcanologists around the world will be able to study the morphologies of the lava tubes with detail and scale previously unavailable.

As the expedition went on, the results came in and the whole team became giddy with Cliff and Guillermo’s success. When Guillermo gave a presentation of his findings on the last night of the expedition, taking us on a 3-D tour of the largest lava cave, the excitement of the team was palpable.

.

This is the magic of citizen science. Not only are the citizen volunteers providing funding and manpower, they’re sharing the inspiration and know-how that accelerates the pace of research, and that is what truly “changes everything.”

.

Sign up for the Earthwatch Newsletter

Be the first to know about new expeditions, stories from the field, and exciting Earthwatch news.