The Jungle of Mirrors, Part 1

A three-part series about the complex history and uncertain future of one of the most biodiverse places in the world—and the people who have dedicated their lives to conserving it.

By Alix Morris

.

Two Rivers Meet in the Forest

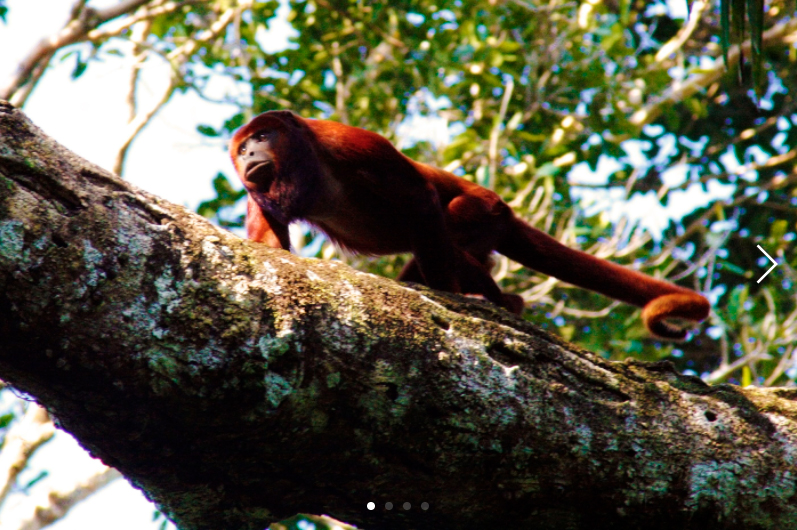

Deep in the heart of Western Amazonia, a flooded forest teems with wildlife. Alligator-like caimans hide in long grasses surrounding lagoons; wading birds hunt for fish in shallow waters; howler monkeys shriek and swing from tree branches; and river dolphins leap from the Samiria River, their reflections rippling in the water alongside them.

The Pacaya-Samiria reserve is the second largest protected area in Peru, a tropical rainforest home to one of the most diverse arrays of plant and animal species in the world. Known as the “Jungle of Mirrors,” the reserve was recently listed as the world’s second “Best Place for Wildlife” by USA Today, after the Galapagos Islands.

.

Red howler monkey

.

Here, human life is frozen in time. Roughly 95,000 indigenous people—most of whom are Cocama Indians—live in the towns and villages in and along the boundaries of the reserve. The Cocama people hunt for bush-meat, tracking pig-like peccaries or large rodents called paca. They fish from small canoes they built with wood from the trees. They live in houses with thatched roofs made from palm fronds they gathered from the forest. They bathe in the rivers. They collect forest fruits. They live as they did centuries ago, relying on the forest’s lush resources to provide them with everything they need to survive.

For the past 10 years, nearly 1,000 Earthwatch volunteers have worked alongside the Cocama to protect this delicate wilderness. At the heart of this mission is a man who has dedicated his life to the preservation of the wildlife and the people who inhabit this reserve: Dr. Richard Bodmer.

Richard and his partners, including the Peruvian government, have developed a tightknit, trusted partnership with the Cocama. With the help of Earthwatch volunteers, Richard provides these communities with information on how wildlife populations are faring to help inform their hunting strategies. By understanding which species are stable and which are in decline, the Cocama can live sustainably within the reserve. This peaceful partnership supports a united mission: protect and conserve the critical rainforest ecosystem. As a direct result of these efforts, wildlife populations that were once endangered have rebounded. Today, the reserve is thriving.

But the story is not quite so simple.

.

Dr. Richard Bodmer welcomes an Earthwatch research team to Pacaya-Samiria.

.

.

The Takeover

In the late 19th century, several indigenous tribes lived along the Pacaya and Samiria Rivers, inside what is now the park reserve. In the 1940s, the Peruvian government decided to turn the flooded forest into a fishing reserve for the Ministry of Fisheries. Fishermen would collect and sell large freshwater fish, locally known as paiche, and profits would fall to the state.

Villages were moved outside the reserve, but the Cocama were allowed to continue to enter the reserve to hunt, to fish, to feed their families.

By the early 1980s, the government had changed the status of Pacaya-Samiria Reserve from fishing to wildlife conservation. It was now a full-time protected area. External funding began to flow in and the Peruvian government enacted a system of park guards to enforce strict controls that would protect the reserve. Any hunting or fishing materials discovered by the guards were immediately confiscated.

But the Cocama knew hidden entrances into the reserve. They developed strategies to evade the guards. During patrols, they hid within the forest; they sank their canoes and catch so they were out of sight. The Cocama believed they needed to protect their food security and provide for their families, before it was too late. Their future was uncertain, their lives were at risk. Poaching was rampant and tension between locals and the government mounted.

.

It was the people’s view that their grocery shop was closing. So their strategy was to take as much as you can as fast as you can. And that of course upset the park guards more because their job was to stop that, and it was getting worse.

— Richard Bodmer

.

The Tipping Point

Gradually, things deteriorated, and conflict between the local people and park guards grew violent. Injuries were frequently reported.

“And then, there was this incident…” recalled Richard.

It was November of 1997. Park guards had confiscated the nets and catch of a group of local fishermen—nets that had been purchased through a loan. In retaliation, the fishermen, armed with machetes, attacked a park station, killing two young biologists and a park guard.

The event made national headlines. The situation was dire. Change was inevitable.

Stay tuned for Part 2 of “The Jungle of Mirrors.”

.

Sign up for the Earthwatch Newsletter

Be the first to know about new expeditions, stories from the field, and exciting Earthwatch news.