.

Bringing Chinampas to the Classroom

By Betsy Anderton

.

At 45 I decided to become a high school teacher.

I hold an undergraduate degree in elementary education, but after two years, I left the field to earn a Ph.D. in Instructional Design and worked within that industry on and off for 20 years. But a desire to work with students, learn about the environment, and support my community led me into the classroom. Not being sure what I wanted to teach, I spent a year subbing in every grade, at every school, for any subject I was offered. Through doing this, I was able to narrow my preferred age to high school. Having three teens of my own at the time, I appreciated the relationships my three daughters had with their teachers and the impact these relationships had on my girls’ self-worth. I spent the next year subbing high school.

.

.

When a position teaching agriculture became available at the nearby high school, I saw a chance to keep hands and minds busy.

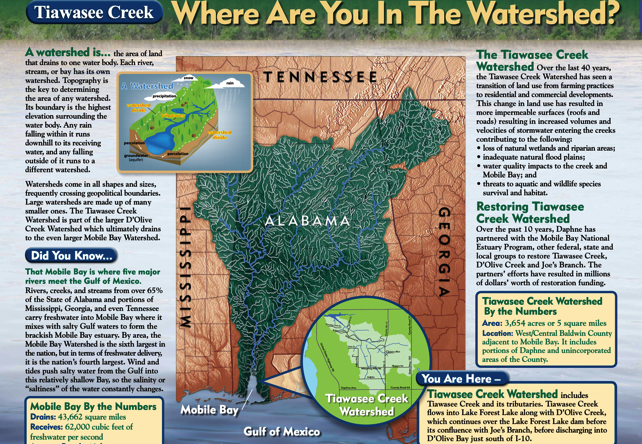

Upon accepting the position I went to have a look at the three acres of farm that were now my responsibility to manage. The place was a mess, from pine trees growing in the greenhouse gutters to weeds neck high. However, being at the top of the watershed for several creeks, perhaps the biggest concern I had was an environmental one. The runoff from the entire school was coming over the farm on its way to the streams and rivers that feed into the Bay and our sensitive estuaries. Not only would the runoff be filled with pollutants, but also the force, amount, and consistency of the water had taken so much topsoil that nothing that could support native wildlife would grow.

Our area in south Alabama, is one of the rainiest in the country, receiving an average rainfall of 69 inches over an average of 59 rainy days each year. The task was overwhelming and at this point I realized how unqualified I was for this job. Stating this to a friend, she quipped back, “Betsy, God doesn’t call the qualified. He qualifies the called. You don’t have to know everything, just show up and start asking people and it will all fall into place”. Well, as an instructional designer trained to work with subject matter experts when building instructional materials, this made a lot of sense.

So in 2017, I showed up and started asking. I mean, I asked everyone and I asked everything and I asked for everything. With the help of Ashley Campbell, the environmentalist for the city, Amy Newbold, who works at the EPA, Wade Burcham, an environmental engineer, and a generous EPA grant, my classes and I began studying and using best management practices to reduce storm water runoff, improve our land, and reduce pollutants entering our waterways. We flew drones to create topographic maps, surveyed the land, used our math skills to determine water velocity, and students volunteered to take water samples after class. In the end, we were able to reduce the transportation of Non-Point Source pollutants (sediment), by 95%.

.

.

It was the success of this project and the desire to learn more about protecting our waterways that first drew my attention to the Earthwatch expedition Conserving Wetlands and Traditional Agriculture in Mexico. The study of traditional farming and wetland preservation in the Mexican chinampas seemed to be dealing with so many of the same issues that impact my wetlands. I also wanted to be able to teach agriculture from a sustainable perspective and the traditional farming methods being supported by this Earthwatch mission would help me achieve this goal.

.

.

In 2019 I designed a Fund for Teachers fellowship to join the expedition and work alongside Dr. Ponce De Leon. In August I travelled to Xochimilco, Mexico. A short walk through town led us to our wooden canal boats that would take us and our equipment through the grid of farm islands—chinampas. The chinampas are built from a layering technique using willow trees as the anchor, then layering mud, branches, reeds, and cane until the island sits high above the water. It’s an ancient system the Aztecs designed to create an agricultural society on a lake. When the Spanish arrived they began filling in more and more of these wetland areas and now, there are only a handful of chinampas being farmed by traditional and sustainable methods.

Not only is the culture of farming on chinampas being threatened but also the resources these practices depend on. Specifically, the quality of water and the sensitive aquatic wildlife dependent on the chinampas ecosystem, most notably, the threatened axolotl salamander.

Throughout the expedition, we canoed to different sites and used our floating laboratories to test for the presence of heavy metals, bacteria and nutrients, which indicate the health of the water. We also collected soil samples at partnering farms and measured changes in water level at select points in our day. After a few days of collecting samples, we were provided with a tour of the University facilities where these samples are further tested and which also house about 20 or so house bred axolotls. Unfortunately, we were not able to find evidence that any of these still exist in the xochimilco, their only native habitat. We did meet an older farmer who recalled swimming in the clean canals, catching the plentiful salamanders and bringing them home to eat.

Not only did we learn methods for testing water and soil in a wetland ecosystem, but were also treated to a day of birdwatching. I was fascinated to realize that so many of the birds migrating from our area on the Gulf Coast make their annual trip to this area of Mexico. Along with all of these experiences, each day we were treated to daily lunches of local foods and stories from the local farmers.

.

.

.

.

.

Upon returning to my classroom and sharing my trip with the students, the landscape class challenged themselves to design and create some model landscapes of historical agriculture. They turned an eroded hillside into a productive terrace and the drain system from the duck pond into a sample chinampa complete with a three sister crop system of corn, beans, and squash. My greenhouse class used the nutrient rich soil from the “chinampa” to support their soil blocking projects. Soil blocking was a method for planting and transplanting seeds I was first introduced to by the farmers on the chinampas. We incorporated traditional strategies for managing pests into our integrated pest management practices on our school farm such as using the appropriate plants to attract beneficial insects and pairing plantings of different plants to deter pests and enrich soil. We also began building habitats for birds and began monitoring the birds coming through our area and comparing them to the birds of the Xochimilco wetlands.

.

The experiences of my Earthwatch expedition reminded me of the importance of being a learner again and the value of hands-on experiences to engage learners

.

It also helped me articulate the relationships between the many subjects my students study, particularly agriculture, history, chemistry, and environmental science. We have continued to build our small farm at school and the native plants we have planted have attracted an abundance of wildlife in what were previously eroded and lifeless spaces. We are now in the process of installing a caterpillar nursery and pollinator garden which has me, once again, looking to Earthwatch!

.

Sign up for the Earthwatch Newsletter

Be the first to know about new expeditions, stories from the field, and exciting Earthwatch news.

.

.

.